This is the third in a series of case studies that use a new methodology to assess the deconstruction potential of new build properties. The case studies and methodology have been funded by the BRE Trust to raise awareness amongst architects, designers and contractors of the potential of Design for Deconstruction (DfD) to create more sustainable buildings and lead to better deconstruction outcomes.

Introduction

A typical specification has been used from a large house builder for 3 and 4 bedroom homes. The majority of new build housing (around 80%) is in the form of a traditional brick and block construction; which means the vast stock of existing housing will also be brick and block. The demolition industry has much experience in demolishing these types of buildings; they are rarely deconstructed largely due to the cost implications and the lack of market for reuse of the components.

Building description

This traditional house has a cavity wall construction with an internal and external skin of brickwork, with a gap between filled with insulation, held together with wall ties, all laid on to a concrete strip foundation. This house will be built up to first-floor level; the internal, load-bearing walls will then be constructed, after which timber joists are added and the build continues up to the timber truss rafter roof level. The building’s specification is summarised in Table 1.

| Construction | Description |

| Foundation | Concrete strip foundation |

| Ground floor | OSB, 240mm timber hoist platform, 130mm rigid PIR insulation, Polythene DPM, In-situ suspended reinforced concrete floor |

| Upper floor | Timber I-joists, mineral wool insulation, chipboard decking |

| External walls | 100mm brickwork, 100mm mineral wool insulation, 150mm block work, plaster board and dab |

| Internal walls | Timber stud walls, insulation, plasterboard |

| Roof | Concrete tiles on softwood battens on reinforced bituminous felt, timber truss rafter roof with mineral wool insulation among the rafters, vapour control barrier, plasterboard |

| Windows | UPVC frame, Double glazed windows GRP roof former window |

| Floor finishes | Carpet, laminate |

| Sanitary ware | Ceramic dual flush WC; sink with low flow taps; wet room with ceramic tiling |

| Services | Condensing boilers (located in kitchen), mechanical extractors to bathrooms, WCs and kitchen |

| Fixtures and Fittings | UPVC fascia, gutters, bargeboards and soffit boards, soil & waste pipes Timber staircase and balustrade |

Table 1: The house’s specification

Project documentation

There is usually no commitment within a housebuilder’s project brief to design for deconstruction. Therefore, there is no active allocation of responsibility for ensuring designing for deconstruction is considered within the project team. Handover packs are usually given to a new homeowner, which has information regards to maintenance etc. It may have details on the construction type and elements used. However it is unlikely to go as far as recording aspects which would be useful for deconstruction.

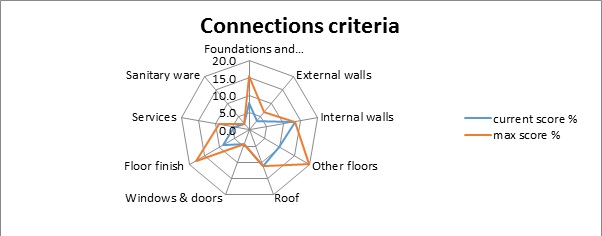

Connections

Overall score 66%

The in-situ solid concrete foundation can be accessed after dismantling external walls. For internal walls, the plasterboard is screwed on to the timber battens and stud walls can be manually un-screwed. Skirting boards nailed to the plasterboard can be removed.

After removing the concrete tiles and softwood battens on the reinforced bituminous felt, the timber truss rafter roof secured to wall plates using truss clips and nails can be dismantled. Similarly, the timber I joist for the upper floors can be taken apart once the carpet and underlay and the tongue and groove chipboards nailed to joists are removed.

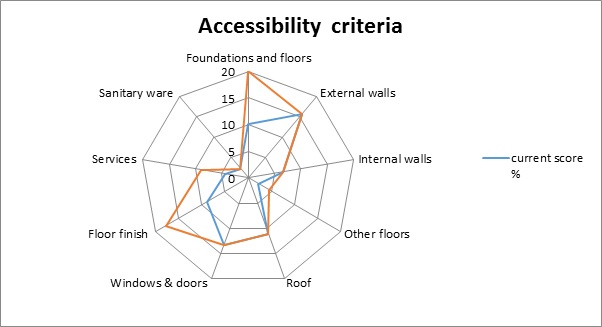

Accessibility

Overall score 74%

The majority of the elements and components are reasonably accessible. Services are relatively straight forward to access, however, it may be difficult to access the services within floor voids unless the carpet is removed. All the horizontal waste pipes, and the heating flow returns to radiators run within the floor voids. Mechanical extraction to the bathroom at the first floor is linked to a tile vent. The boiler in the ground floor allows good level of access for service and to dismantle/ remove any machinery.

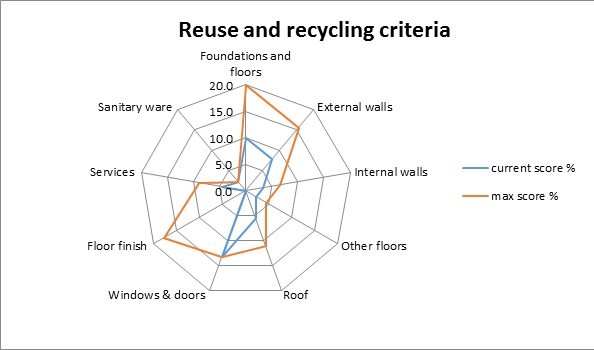

Reuse and recycling potential

Overall score 49%

Recycling of the concrete slab is possible depending on whether it is possible to separate and sort steel and concrete cost-effectively. There are no commercial recycling options for rigid foam insulation at present. The external brick leaf of the cavity wall is likely to be unsuitable for reuse due to the cement used and can be recycled as aggregate along with the blockwork.

Fibre cement slates are recyclable, though there is currently no end market. The timber battens are recyclable, with an estimated 30-40% reusable.

The vapour barrier, bitumen felt, mineral wool and OSB are currently difficult to recycle.

The roof joists are recyclable; they could also theoretically be reused, though this is rare. The timber truss, and the metal connecting plate could be reused and/or recycled.

For the internal stud walls, around 20%-30% of timber stud is reusable. The rest of the timber can be recycled. The plasterboard could also be recycled.

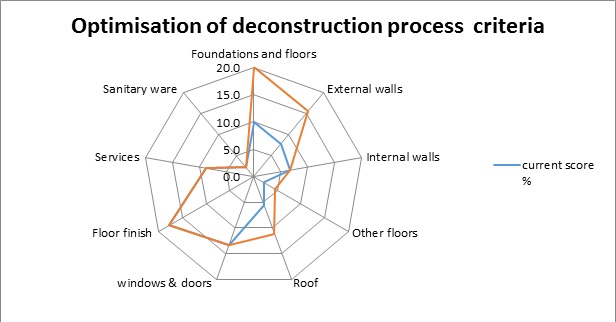

Optimisation of deconstruction

Overall score 86%

The internal floor finishes, doors and fittings can be soft stripped manually, with hand tools to minimise damage caused by large machinery. Following this, it is possible to strip out the main building components such as the roofing, windows and finally framing and foundations can be done with excavators or cranes. This may have to be followed by more detailed manual separation of individual fixings and components (either on-site or off-site). Timber floors and fittings may require soaking with water to avoid splitting prior to removal.

Standard construction equipment can be used to demolish the cavity wall. No special tools would be required.

Fixture and fittings

The WC and the sink could be reused again; though this is currently rare. The tiles in the wet room and the taps etc could be recycled.

It is currently difficult to recycle carpet and laminate flooring; the carpet is likely to be unsuitable for reuse, however the laminate flooring could be lifted up for reuse, though care would need to be applied, if it is glued. The windows are of a standard size and are therefore suitable for reuse.

Summary

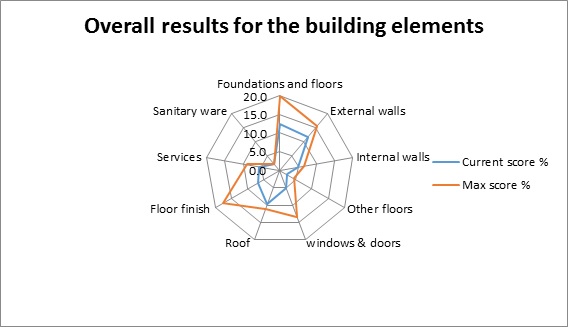

Figure 1: The overall DfD results for the house’s building elements

The traditional house specification scored 61% overall for its DfD potential. Figure 1 shows the overall score by element. Elements which had greater potential for DfD are the timber components (battens, roof truss and joist) and sanitary ware items, windows and doors. Optimisation of the deconstruction process (81%) and the accessibility criteria (70%) scored the highest and reuse and recycling potential the lowest (44%). This is not surprising as whilst many of the components can be recycled, few lend themselves to reuse.

Key issues summarised are:

- The demolition industry is well practised in demolishing brick and block housing where high recycling rates can be achieved; however the reuse of components is usually very low or non-existent.

- Some common materials/products used are currently difficult to recycle such as the mineral wool, bitumen felt and vapour control barrier.

- Cement mortar is typically used for the brickwork and as it is difficult to remove from the bricks, it makes them unsuitable for reuse

- The timber components do lend themselves to reuse, however new materials are often cheap to buy, making reuse an unattractive option

- Sanitary ware items, windows and doors, do have a reuse potential, but remain unused, due to a lack of demand.

- The design of a brick and block house lends itself to being soft stripped before demolition is undertaken. Therefore there is an opportunity to salvage certain items for reuse.

- The time and effort to deconstruct a house compared to demolition will be greater (2 to 3 times), meaning that there will be a higher cost attached.