The Association for the Conservation of Energy (ACE), working in partnership with CAG Consultants, have published the Warm Arm of the Law, an Ebico Trust funded (through any profit made by the energy supplier Ebico) research project looking at the extent to which the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) and Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) are being proactively implemented and enforced by local authorities across England and Wales. Ian Watson, of BRE’s Housing & Health team, writes.

The Association for the Conservation of Energy (ACE), working in partnership with CAG Consultants, have published the Warm Arm of the Law, an Ebico Trust funded (through any profit made by the energy supplier Ebico) research project looking at the extent to which the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) and Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) are being proactively implemented and enforced by local authorities across England and Wales. Ian Watson, of BRE’s Housing & Health team, writes.

The project was overseen by a steering group involving the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the Local Government Association, the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health, the Association of Local Authority Energy Officers and the Residential Landlords Association.

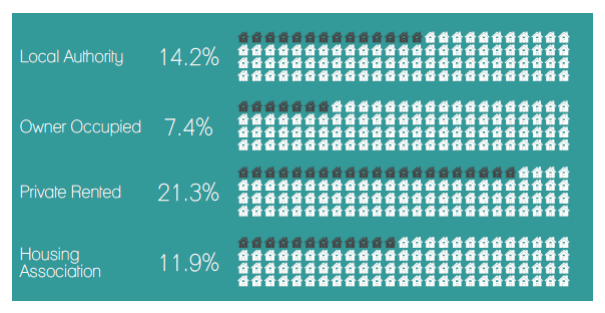

The Private Rented Sector (PRS) has grown by over 40% in the last ten years and now comprises 20.5% of the housing market in England, compared to just 10% in 1999. Fuel poverty continues to be a major problem and is particularly acute in the PRS, with an estimated 21% of households thought to be in fuel poverty compared with other tenures, the PRS in England has the largest proportion of energy inefficient F and G rated properties. Source: https://www.ukace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Ebico-Policy-Report.pdf page 14

The Private Rented Sector (PRS) has grown by over 40% in the last ten years and now comprises 20.5% of the housing market in England, compared to just 10% in 1999. Fuel poverty continues to be a major problem and is particularly acute in the PRS, with an estimated 21% of households thought to be in fuel poverty compared with other tenures, the PRS in England has the largest proportion of energy inefficient F and G rated properties. Source: https://www.ukace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Ebico-Policy-Report.pdf page 14

As BRE have estimated the financial cost to the NHS from poor energy efficiency in the PRS, analyse the data generated by English Housing Survey surveyors for reporting to central government, and provide assistance to local authorities on better understanding their local position in terms of numbers and local distributions of private rented households and energy efficiency, they were invited to take part in the research (a lengthy stakeholder telephone interview took place in December 2017). The interview elicited views on how effective HHSRS/MEES are or could be in terms of raising the energy efficiency of privately rented properties.

The headline finding from the research is that local authorities are not doing enough to enforce minimum energy efficiency standards in the PRS. This is hardly surprising given the budget cuts, with local authorities reducing spend on enforcement activity by a fifth between 2009/10 and 2015/16. Stakeholders reported mixed feelings about HHSRS, with some finding it useful for dealing particularly with cold hazards which may pose serious health concern and where there is no financial contribution limit, while others argued the guidance is ambiguous. The introduction of simple minimum energy efficiency standards under MEES was felt by some to be a positive step, although some stakeholders felt it could only be effective if amended and additional resources made available for enforcement. Stakeholders also felt that there was a lack of clarity on how these two systems could work together.

The headline finding from the research is that local authorities are not doing enough to enforce minimum energy efficiency standards in the PRS. This is hardly surprising given the budget cuts, with local authorities reducing spend on enforcement activity by a fifth between 2009/10 and 2015/16. Stakeholders reported mixed feelings about HHSRS, with some finding it useful for dealing particularly with cold hazards which may pose serious health concern and where there is no financial contribution limit, while others argued the guidance is ambiguous. The introduction of simple minimum energy efficiency standards under MEES was felt by some to be a positive step, although some stakeholders felt it could only be effective if amended and additional resources made available for enforcement. Stakeholders also felt that there was a lack of clarity on how these two systems could work together.

Source: https://www.ukace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Ebico-Toolkit.pdf page 10

The published 140-page report makes a number of recommendations including:

- National government needs to ensure that local government is adequately resourced to proactively implement both MEES and HHSRS and could offer guidance and advice on how these services can be implemented as cost effectively as possible.

- Local government needs to develop a joined-up approach to implementing HHSRS and MEES. National government could assist by issuing guidance and examples of how best to do this.

- Using HHSRS where an exemption has been lodged for MEES (e.g. in relation to the cost cap) and where a Category 1 Excess Cold hazard is anticipated to exist.

- Requiring EPC information to be collected as part of any selective and HMO licensing schemes in order to support the enforcement of HHSRS and MEES.

- Update the HHSRS Operating Guidance, particularly the health outcome statistics, definition of affordability and relationship between energy efficiency ratings and excess cold hazards.

BRE’s work in this area is referenced on a number of occasions, including:

- research into the health costs of cold homes in the private rented sector (pages 6 & 15).

- the Excess Cold Calculator (XCC) – “it was suggested that local government should have open access to BRE’s Excess Cold Calculator to enable them to successfully build a thorough evidence base for Tribunal appeals.” (page 64), with the recommendation to “Provide open access to BRE’s Excess Cold Calculator to enable councils to build the evidence base to take to Tribunal appeals.” (page 87).

- Liverpool’s use of the HHCC – “Another stakeholder noted that Liverpool City Council “secured £12million from landlords through being proactive and looking at housing in a zonal way”. The council were said to be proactive in improving properties before enforcement action was taken, and that they were able to secure buy in from statutory agencies through promoting the BRE’s Housing Health Cost calculator (which predicts avoidable costs to health sector from Category 1 and 2 hazards).” (page 70 – not completely factually correct, but we’ll take it!)

With the document widely promoted and circulated amongst local and central government, landlords and energy companies, the profile BRE enjoys in this sector is reinforced. For more on BRE’s work in this area, go to www.bregroup.com/housingstock or contact the team at [email protected].